We're working on getting insights, tools, and techniques straight to your inbox on a weekly basis. No commitment required, we'll reach out again when we're ready to see if you still want to receive weekly emails.

By submitting this form, you agree to receive recurring marketing communications from Piar at the email you provide. To opt out, click unsubscribe at the bottom of our emails. By submitting this form, you also agree to our Terms & Privacy Policy

High-performing communications teams build habits on more than skills and planning. Growth emerges from structured reflection. When bias learning becomes a fixture (not an afterthought) in annual development programs, the result is a workforce that adapts to evolving narratives and audience needs while strengthening credibility, both internally and externally.

Research demonstrates that experiential learning produces measurably better professional outcomes than traditional training approaches. Experiential learning is defined as a hands-on educational process that produces knowledge and skills through a combination of experience, reflection, conceptualization of the experience, and use of learned ideas to make decisions or solve problems. This mode of learning proves particularly valuable when professionals seek to gain understanding of various challenges, assess whether their skill sets align with situational demands, and further develop transferable skills to make informed decisions.

The motivation for incorporating experiential learning into professional development stems from well-established concepts of self-efficacy. Albert Bandura described how practicing and experiencing a specific task leads to increased confidence in a person's ability to perform that task, with this positive belief feeding back into better performance. Self-efficacy is experience-based and serves as a foundation for successful performance. Research at the undergraduate level has proven that hands-on experiences effectively build self-efficacy and skills, two variables that predict aspirations for professional advancement.

A 2025 study by the National Association of Colleges and Employers surveyed early career professionals who graduated in 2021, 2022, and 2023 to determine if (and how) experiential learning impacted their careers after landing their first jobs. The results showed that those who took part in experiential learning had higher rates of career satisfaction and a higher average salary than those who did not engage in experiential learning. These findings suggest that experiential learning meets goals of helping professionals identify their best career paths, engage in opportunities for mentorship and networking, and enhance their career prospects. The benefits extend beyond initial job offers to career progression and long-term satisfaction.

Experiential learning differs fundamentally from traditional professional development. Research examining workplace learning notes that experiential learning opportunities allow professionals to be immersed in actual (or simulated) work environments, acquire and apply skills needed in particular contexts, and complete hands-on projects directly related to their profession. This contrasts with passive information transfer where professionals sit through presentations without engaging with the material in ways that change practice.

Reflective practice represents a cornerstone of professional development. Research published in PMC defines reflective practice as the practice of thinking about and critically analyzing one's actions with the goal of changing and improving professional practice. Reflective practice guides deeper insights for analyzing experiences that reveal new meanings, drive improvement, and help identify knowledge gaps, all of which catalyze new thinking and responses contributing to continuous knowledge improvement.

David Kolb's learning cycle, developed in 1984, highlights reflective practice as a tool to gain conclusions and ideas from experience, with the aim of taking learning into new experiences and completing the cycle. Kolb's cycle follows four stages: concrete experience (trying something new), observation and reflection on that experience, abstract conceptualization (drawing on ideas from research and previous knowledge), and active experimentation (testing ideas in future situations). This cycle maps directly to how communications professionals can learn from campaign outcomes.

Research examining reflective practice across higher education and professional contexts found that reflection plays a foundational role in supporting professional development. The research identified eight principles for effective reflective practice: reflection requires purpose and intention, reflection connects

to practice improvement, effective reflection involves both individual and collaborative processes, reflection benefits from structured frameworks, reflection develops through scaffolding and support, reflection produces actionable insights, reflection requires safe environments for honest examination, and reflection becomes most valuable when embedded in regular practice rather than treated as separate activity.

Studies on reflective practice as fuel for organizational learning demonstrate that reflection lies at the heart of learning and professional growth. Learning theorists assert that organizational learning happens at three intertwined levels: individual, group, and organization. Reflective practices guide deeper insights that reveal new meanings, drive improvement, and identify knowledge gaps. Meaningful reflective practice develops a growth mindset enacted through mindful presence, asking questions, and taking action.

For communications teams, this research suggests that simply reviewing campaign metrics or discussing what worked misses the deeper learning available through structured reflection. Teams need frameworks that prompt examination of assumptions, biases in decision-making, and patterns in how they respond to challenges. The cognitive bias lens provides exactly this framework.

The after-action review (AAR) represents one of the most successful organizational learning methods ever developed. Originally created by the U.S. Army in the 1970s, AARs help teams learn from both mistakes and achievements. The method has since been adopted by many organizations for performance assessment. AARs differ from traditional debriefs by beginning with clear comparison of intended versus actual results achieved and remaining forward-looking, with the goal of informing future planning, preparation, and execution.

Research demonstrates that well-conducted AARs can improve team effectiveness by 25% across a variety of organizations and settings. The method works because it creates structured opportunities for collective sensemaking where teams develop shared understanding of what happened and why. AARs have been successfully implemented in medical fields, fire services, aviation, education, and various organizational training environments.

A study examining AAR effectiveness in healthcare settings found that routine application of AARs led to significant improvements in learning efficacy. The research highlighted limitations of the traditional belief that change programs will succeed if people are well-educated and informed about best practice. Simply telling people what to do differently does not bring about required change. When teams include people in learning from events and ask them to reflect and learn (as happens with the AAR process), outcomes prove far more effective and sustained.

Research published in Better Evaluation notes that organizational learning requires continuous assessment of organizational performance, examining successes and failures to ensure that learning takes place supporting continuous improvement. The systematic application of properly conducted AARs across an organization can help drive organizational change. Beyond turning unconscious learning into explicit knowledge, AARs help build trust among team members and overcome fear of mistakes. When applied correctly, AARs become a key aspect of internal systems for learning and motivation.

For communications teams, AARs provide a natural structure for examining how cognitive biases influenced campaign planning and execution. Rather than generic project retrospectives, bias-focused AARs ask specific questions: Where did confirmation bias lead the team to favor data supporting initial hypotheses while dismissing contradictory evidence? How did anchoring on the first creative concept prevent consideration of alternatives? When did groupthink pressure suppress dissenting voices that might have improved outcomes?

The concept of communities of practice provides theoretical foundation for understanding how professionals learn together. First proposed by cognitive anthropologist Jean Lave and educational theorist Etienne Wenger in 1991, communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly. The process by which community members become part of a community occurs through legitimate peripheral participation, where newcomers initially observe and perform simple tasks while learning community norms and practices before taking on more complicated work.

Wenger's work on communities of practice identifies three structural characteristics: a domain of knowledge that creates common ground and guides learning, a community that creates the social fabric for learning and encourages collaboration, and a practice representing the shared repertoire of resources that members develop over time. For communications teams, the domain might be strategic messaging or media relations, the community comprises team members and their collaborative relationships, and the practice includes the tools, frameworks, and approaches the team develops through working together.

Research examining professional learning communities in organizational contexts found that effective professional learning communities emphasize job-embedded learning and development. This refers to professional learning in the organizational context that focuses on problems of practice and utilizes real work examples. Research relates professional learning to both individual and collaborative practices, emphasizing both forms as core processes required in professional development and organizational evolution.

A comprehensive review of professional learning community research examined studies on the impact of professional learning communities on practice and outcomes. While few studies moved beyond self-reports of positive impact, empirical studies exploring actual impact on practice and outcomes found that well-developed professional learning communities have positive effects on both professional practice and performance. The collective results suggest that learning communities work when they create genuine opportunities for collaborative learning focused on real challenges rather than abstract concepts.

For communications teams embedding bias learning, the community of practice framework suggests that learning happens through participation in shared work. Teams develop common language for discussing bias, build shared repertoires of examples and patterns, and create collective memory of how bias has influenced past work. This collective learning proves more powerful than individual awareness because it becomes embedded in team culture and practice.

Begin by mapping training and development alongside the team's actual year-in-review. For each quarter, pair campaign outcomes and major messaging initiatives with reflection modules that focus on specific cognitive bias patterns observed in the reporting or delivery process. Bias learning in this context draws on experiential review: discussion led by those who worked on the campaigns.

Research on experiential learning in professional development emphasizes that individuals should conduct their own needs analysis to ascertain what gaps exist in their professional development. For communications teams, this means examining which cognitive biases most frequently affect their work. Teams working in fast-paced news cycles may struggle most with availability bias (overweighting recent events) and anchoring (fixating on first information received). Teams managing long-term reputation building may face more challenges with confirmation bias (seeking data supporting preferred narratives) and groupthink (suppressing dissent to maintain team harmony).

Content lives in accessible places: regular team calls, offsite learning sessions, even short asynchronous video lessons. Research on professional learning communities found that effective professional development is collaborative and collegial, practice-oriented, combining working and learning. These are key features that make learning stick. Traditional professional development activities such as off-site workshops, informative meetings, courses, and training sessions prove not very effective. The focus of research into professional professionalization has shifted to workplace learning: learning situated at the workplace, through work and for work.

Avoid forced theory. Root each session in practical examples delivered with reference to current or past work at the organization. Questions are open and collaborative: Where did outside events overtake the plan? Which stakeholder perspectives received extra weight, and why? How did the first pitch concept presented influence all subsequent creative development? When did the team's desire for consensus prevent examination of alternative approaches?

Research on reflective practice in organizational learning suggests that reflection develops through asking specific questions that stimulate inquiry and critical thinking. For communications teams examining bias, these questions might include: What assumptions did we make at the start of this campaign? What evidence did we seek out, and what evidence did we ignore? How did the composition of our planning team affect the range of perspectives considered? What would someone with the opposite view say about our approach?

Encourage teams to document what they find. These short write-ups build a knowledge archive tailored to the organization's strengths and weaknesses, creating feedback that goes beyond routine project-based reviews. Research on organizational knowledge management demonstrates that many organizations use databases or blogs to make lessons from AARs available via intranet to all teams. The J.M. Huber Corporation uses AARs after every planned project and significant unplanned event, with employees posting learnings to a database and creating online after-action reports that include action plans and lessons learned. Other employees worldwide can search the database to find AARs on topics related to their work.

When used as part of annual evaluation, these notes show where the team adapted most and where invisible patterns still need to shift. Research on after-action reviews found that AARs are effective communication tools for promoting organizational reliability if held regularly. Firefighters surveyed about their most recent AAR showed that freedom of dissent attenuated the negative influence of ambiguity on AAR satisfaction. This suggests that creating environments where team members can speak freely about what they observed improves both satisfaction with the learning process and the quality of insights generated.

The knowledge archive serves multiple purposes. New team members can review past campaigns to understand typical bias patterns affecting the organization. Senior leaders can identify systemic issues requiring structural changes rather than individual behavior modification. The archive creates organizational memory that persists despite staff turnover. Most importantly, documenting bias patterns makes them discussable. What was once invisible (groupthink suppressing alternatives) or unnameable (anchoring on the first creative concept) becomes part of shared team vocabulary.

Research on communities of practice and knowledge development notes that knowledge is shared through storytelling, which allows workers to explicate problems and build stories together that invent solutions. For communications teams, the bias learning archive functions as a collection of stories about how bias affected past work and how teams successfully mitigated those effects. These stories become resources that help team members recognize similar patterns in new situations.

Tie the reflection process directly to talent development and recognition. Teams see bias learning as a core value, which supports recruitment, client confidence, and upskilling. Research examining professional development and career outcomes found that professionals who engaged in experiential learning demonstrated higher career satisfaction, higher average salaries, and better career progression than those who did not. These findings suggest that experiential learning delivers on its promise to enhance career prospects.

Communications professionals increasingly recognize that awareness of cognitive bias represents a valuable professional skill. Job candidates who can articulate how they identify and mitigate bias in communications planning demonstrate more sophisticated strategic thinking than those who focus only on tactical execution. Teams that embed bias learning into development programs send clear signals about organizational values and standards for professional excellence.

Research on professional learning communities and teacher performance found that all dimensions of professional learning communities (shared values and vision, shared and supportive leadership, supportive conditions, collective learning and application, and shared personal practice) positively correlate with performance. Interestingly, shared values and vision indirectly influenced performance by mediating the other dimensions. For communications teams, establishing shared values around recognizing and mitigating bias creates foundation for all other learning activities.

Recognition programs can highlight teams or individuals who demonstrated exceptional bias awareness during campaign planning. Annual reviews can include assessment of how team members contributed to collective learning about bias. Promotion criteria can incorporate demonstrated ability to identify cognitive shortcuts affecting strategic decisions. These formal signals reinforce that bias learning matters for professional advancement, not just campaign outcomes.

Research on workplace learning and professional development found that continuous professional development assists professionals in responding to evolving needs, applying new strategies, supporting career advancement, and fostering personal and professional growth. Through reflection, professionals learn from experiences and apply knowledge to assist in future decision-making. The process of reflection promotes the critical continuous learning and improvement that professionals need and can ultimately guide them toward more fulfilling and purposeful career experiences.

Start with a pilot program focused on one quarter's worth of campaigns. Select three to five campaigns representing different types of communications work (media relations, content strategy, crisis response, stakeholder engagement). For each campaign, convene the core team for a 90-minute AAR focused specifically on cognitive bias.

Use a structured framework to guide discussion:

What was intended? Review the original campaign plan, objectives, and assumptions. What did the team believe would happen? What evidence supported those beliefs?

What actually happened? Examine outcomes without judgment. Where did results align with intentions? Where did they diverge?

What cognitive biases may have influenced planning or execution? This is where the bias learning occurs. Did the team anchor on early concepts? Did confirmation bias lead to ignoring warning signs? Did availability bias cause overweighting of recent events? Did groupthink suppress alternative approaches?

What will we do differently? Identify specific actions to mitigate identified biases in future work. These might include structured techniques (devil's advocate roles, pre-mortem exercises, diverse review panels) or process changes (mandatory waiting periods before finalizing decisions, requirements to document alternatives considered).

Research on AAR implementation recommends that organizations make participation mandatory and involve all team members in discussion, even customers, partners, and suppliers when relevant. Gather relevant facts and figures related to performance. If deadlines were missed, standards were ignored, or feedback was disregarded, these facts set foundation for discussion grounded in relevant data.

Document each AAR in a standardized format and add it to the shared knowledge archive. Tag each entry with the cognitive biases identified and the mitigation strategies developed. Over time, patterns will emerge showing which biases most frequently affect specific types of campaigns or certain team configurations.

After completing the pilot, assess impact. Did teams report greater awareness of cognitive shortcuts? Did subsequent campaigns show evidence of better decision-making? Did team members reference bias concepts in planning discussions? Use these insights to refine the program before expanding to all campaigns.

Research on evaluating professional learning recommends measuring impact through multiple methods: participant reactions (satisfaction with the learning process), learning outcomes (demonstrated understanding of concepts), behavior change (application of learning in practice), and results (improvement in performance outcomes). Communications teams can track all four levels by surveying participants, testing bias recognition skills, observing team interactions, and analyzing campaign outcomes.

The challenge is not launching a bias learning program but sustaining it as organizational priority. Research on organizational learning notes that efforts to bring AAR practices into corporate culture most often fail because people reduce the living practice to a sterile technique. Used regularly to assess successful and unsuccessful events, AARs strengthen teams and improve performance and can become ingrained into organizational DNA. When key learnings from AARs are shared, the experiences of one team can benefit the entire organization.

To build sustainability, integrate bias learning into existing organizational rhythms. If the team holds quarterly business reviews, add a bias learning module examining that quarter's work. If annual planning sessions gather the full team, include time for reviewing bias patterns from the previous year and identifying mitigation strategies for the year ahead. If new team members complete onboarding programs, include orientation to the bias learning framework and the knowledge archive.

Create informal opportunities for bias discussion beyond formal AARs. When teams gather for project kickoffs, prompt brief consideration of which biases might affect this particular initiative given its characteristics and constraints. During campaign execution, create psychological safety for team members to flag potential bias in real-time. After campaign completion, celebrate teams that successfully identified and mitigated bias even if campaign outcomes fell short of goals in other ways.

Research on professional learning communities found that school context factors significantly affected community development. A proactive, stimulating role of organizational leaders, the presence of collective autonomy and skilled facilitators, the quality of discourse, and the degree of organization and structure of meetings all matter for development. Sufficient time and space were considered indispensable. These findings confirm that organizations must create supportive conditions if they want learning communities to flourish.

Assign responsibility for maintaining the bias learning program. This might be a rotating role among senior team members or a standing responsibility for whoever leads professional development. The responsible person ensures AARs happen on schedule, facilitates discussions, maintains the knowledge archive, identifies patterns across multiple campaigns, and champions bias awareness in organizational culture.

Communications leaders need evidence that bias learning improves outcomes, not just awareness. Measurement should examine multiple levels of impact.

At the individual level, assess whether team members can identify cognitive biases in sample scenarios. Present case studies of communications challenges and ask team members to identify which biases might affect decision-making and what mitigation strategies they would recommend. Track improvement over time as individuals develop bias recognition skills.

At the team level, analyze whether teams that engage in bias learning demonstrate different decision-making patterns than teams that do not. Do they consider more alternatives before finalizing approaches? Do they seek out disconfirming evidence more actively? Do they show less anchoring on initial concepts? These behavioral changes can be observed through meeting notes, planning documents, and team member reports.

At the campaign level, examine whether campaigns planned with explicit bias awareness show better alignment between intentions and outcomes. Do these campaigns encounter fewer unexpected obstacles? Do they adapt more quickly when circumstances change? Do they achieve objectives more consistently? These outcome differences demonstrate the business value of bias learning.

Research on learning outcomes and evaluation suggests that comprehensive evaluation examines cognitive outcomes (understanding of concepts), skill-based outcomes (ability to apply concepts), and affective outcomes (attitudes and motivation). For communications teams, cognitive outcomes include ability to define and recognize biases, skill-based outcomes include ability to implement mitigation strategies, and affective outcomes include willingness to acknowledge bias and engage in reflective practice.

Build measurement into the program from the start rather than adding it as an afterthought. Collect baseline data before launching the bias learning program to establish comparison points. Use consistent measures over time to track progress. Share results with teams to demonstrate impact and maintain engagement.

If your team ever pauses to ask where thinking drifted or how habits shaped decisions, this Bias Spotter might help. Each section matches a bias seen often in communications work, with prompts to make discussions easier in reviews or learning sessions.

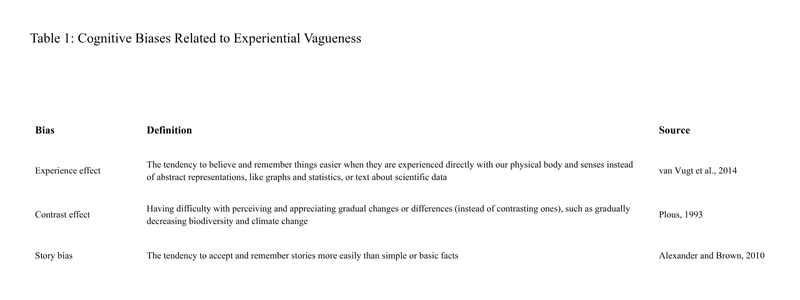

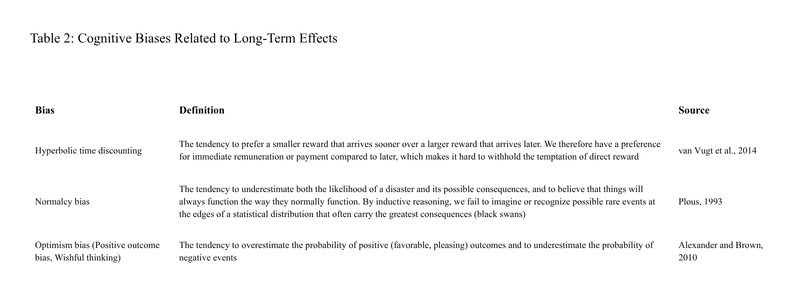

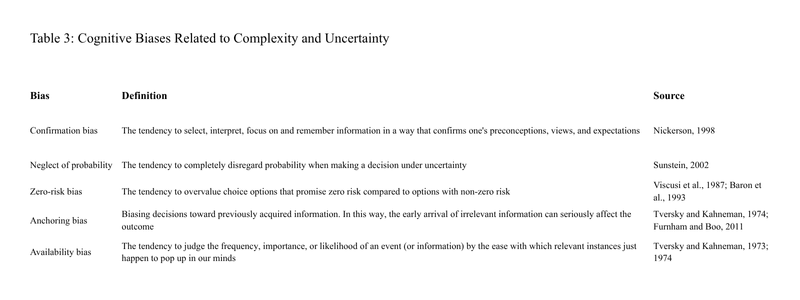

The tool includes frameworks for identifying:

Download and use it for free at the resource link above.

…

Tanzeel “Tan” Sukhera is the Co-founder & CEO of Piar. Tan is based in Montreal, and has 7 years of experience in Media Monitoring & Social Listening, PR & Comms Measurement, Strategy & Analysis. Through events and workshops, Piar helps PR and communication leaders apply behavioral decision science to real-world campaigns, messaging, and stakeholder work. Learn more or reach out at piar.co.

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/tsukhera/ 👈