We're working on getting insights, tools, and techniques straight to your inbox on a weekly basis. No commitment required, we'll reach out again when we're ready to see if you still want to receive weekly emails.

By submitting this form, you agree to receive recurring marketing communications from Piar at the email you provide. To opt out, click unsubscribe at the bottom of our emails. By submitting this form, you also agree to our Terms & Privacy Policy

Effective teams understand the behavioral signals that shape how members collaborate. A systematic self-audit using psychological safety, feedback quality, and role clarity puts real dynamics into focus, making strengths and pain points visible for everyone involved. This approach encourages team members to be honest about habits that often go undiscussed: openness to new perspectives, willingness to address tough topics without fear, and everyday practices in sharing responsibility and making group decisions.

Google spent years analyzing what separated their highest-performing teams from average ones, interviewing hundreds of teams across the organization. Their Project Aristotle initiative, led by Julia Rozovsky, initially assumed the answer would involve putting smart people together with clear structure. The findings went in a different direction.

After analyzing 180 teams, researchers discovered that intelligence, individual performance metrics, and team composition mattered far less than a single factor: psychological safety. Teams where members felt comfortable expressing thoughts and ideas openly, where people could take interpersonal risks without fear of embarrassment or punishment, consistently outperformed their peers. The difference showed up in meeting participation rates, in how quickly teams spotted and corrected errors, and in their ability to generate innovative solutions under pressure.

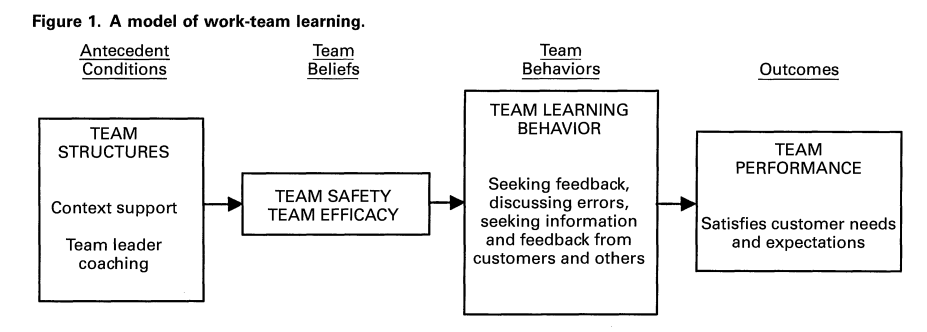

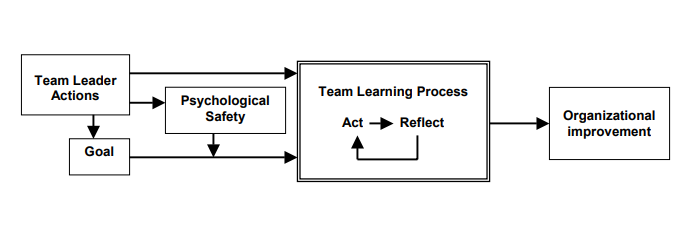

Amy Edmondson's 1999 study of 51 work teams at Harvard laid the groundwork for understanding why. Her research demonstrated that psychological safety acts as an engine for team learning behavior. Teams with high psychological safety engaged more frequently in asking questions, seeking feedback, discussing errors, and testing new approaches. This learning behavior then mediated the relationship between safety and performance. The teams that felt safe enough to learn together performed better because they caught and corrected mistakes faster (Edmondson, 1999).

Communications work involves constant judgment calls under uncertainty. Which stakeholder concern gets priority, how to frame an opening line, when timing feels right for an announcement. These micro-choices run on mental shortcuts developed through experience, but when context shifts, those shortcuts can produce unexpected outcomes.

A 2020 study published in Frontiers in Psychology examined how psychological safety actually translates into team effectiveness. The research found that psychological safety did not directly drive team effectiveness but worked through two pathways. First, safety increased team learning behavior, which then improved performance. Second, safety boosted team efficacy (the shared belief that the team can execute tasks successfully), which also improved performance. The direct path from safety to effectiveness showed no significant effect (Kim, Lee, & Connerton, 2020).

This means psychological safety functions as Edmondson described it: as an engine rather than fuel. It creates conditions where other beneficial team processes can occur. For PR teams conducting self-audits, this distinction matters because you cannot simply declare "we have psychological safety now" and expect performance to jump. The safety has to enable specific behaviors: more open information sharing, more willingness to discuss what went wrong in past campaigns, more comfort in raising early warning signals about stakeholder reactions. These behaviors, repeated over time, build the learning patterns that drive results.

A comprehensive 2017 meta-analysis by Frazier and colleagues examined 136 independent samples representing over 22,000 individuals and nearly 5,000 groups to understand psychological safety's effects. The research confirmed that psychological safety predicted team learning behavior, creativity, and performance across diverse contexts, team types, and organizational settings. The effect sizes were moderate to large, meaning psychological safety explained meaningful variance in outcomes (Frazier et al., 2017).

The same meta-analysis examined what built psychological safety in the first place. Leader inclusiveness (welcoming input, acknowledging contributions, addressing concerns raised by team members) showed the strongest relationship. This confirms that psychological safety primarily originates from leadership behavior rather than team member personality traits or organizational policies. You can hire naturally confident people and still create low psychological safety through dismissive or authoritarian leadership. You can build high psychological safety with initially hesitant team members through consistently inclusive practices.

Research on Norwegian management teams, published in 2022, examined whether psychological safety's effects on team effectiveness operated through behavioral integration. The study of 160 management teams found that psychological safety increased team effectiveness specifically by enabling behavioral integration, which refers to the extent to which team members engage in mutual collaboration, information sharing, and collective decision ownership (Mogård et al., 2022).

The research demonstrated that psychological safety and team effectiveness had no direct relationship. Instead, safety created conditions for collaborative behavior, and collaboration drove results. Teams with high psychological safety showed different patterns in how they received and acted on feedback. Rather than defensive responses or superficial acknowledgment followed by no change, psychologically safe teams treated feedback as information worth investigating. They asked clarifying questions, tested whether the feedback aligned with other signals they had noticed, and experimented with adjustments while tracking whether those adjustments improved outcomes.

These findings point to a common misconception about psychological safety. It does not mean everyone naturally feels comfortable speaking up because the team has nice people who treat each other kindly. Nice teams can still have low psychological safety if the structural conditions do not support risk-taking. Someone can be personally warm while also dominating every discussion, leaving no space for others to contribute. Someone can be individually encouraging while working within a performance management system that punishes visible failures, creating strong incentives to hide problems rather than surface them early.

Routine self-assessments give teams a chance to catch issues before they become embedded in company culture. The framework anchors this audit around key behavioral indicators that research has validated as meaningful predictors of team effectiveness.

Start with collaborative problem-solving visibility. How often do team members actively work together to resolve challenges, rather than escalating immediately to leadership or waiting for formal problem-solving sessions? The Norwegian research found that teams where members regularly engaged in mutual collaboration, information sharing, and collective decision ownership performed significantly better on both task performance and individual satisfaction measures. The relationship between psychological safety and team effectiveness was fully mediated by this collaborative behavior, meaning safety created the conditions for collaboration, and collaboration drove results (Mogård et al., 2022).

Track responsiveness to constructive feedback as a distinct indicator. Research consistently shows that teams with high psychological safety demonstrate different patterns in how they receive and act on feedback. Psychologically safe teams treat feedback as information worth investigating. They ask clarifying questions, test whether the feedback aligned with other signals they had noticed, and experiment with adjustments while tracking whether those adjustments improved outcomes.

Monitor role clarity, particularly during periods of organizational change. When scope shifts, when priorities realign, when team composition changes, does everyone maintain a clear understanding of their responsibilities and decision rights? Or does ambiguity creep in, creating redundant work in some areas and gaps in others? The research on team effectiveness consistently identifies role clarity as a foundational enabler of performance. Without it, teams struggle to coordinate their efforts effectively.

Rate these elements across the group using a simple five-point scale. The act of rating forces specificity. "We communicate well" means nothing actionable, but "our team scored three out of five on responding constructively to feedback because we tend to get defensive when clients question our recommendations" identifies a specific behavior pattern that can be addressed.

Share results in open discussion. This step matters more than the actual scores because the conversation reveals why team members rated items differently, what specific incidents shaped their assessments, and where perceptions diverge. These discussions defuse blame by focusing on patterns rather than personalities. When someone consistently interrupts others in meetings, framing that as "we scored low on equal participation" creates space to address the behavior without making it personal.

Teams who repeat the audit quarterly build a track record they can learn from. Patterns emerge that single snapshots miss. A dip in psychological safety scores often precedes visible performance problems by several weeks, while an improvement in feedback responsiveness correlates with faster campaign iteration cycles. These longitudinal patterns help teams become proactive.

The Norwegian study examined psychological safety across teams ranging from 3 to 19 members over multiple measurement periods. Teams maintaining high psychological safety showed consistent behavioral integration, which in turn predicted sustained high performance. Teams where safety fluctuated experienced corresponding fluctuations in collaborative behavior and outcomes, suggesting that psychological safety requires ongoing maintenance (Mogård et al., 2022).

Consider what this means for annual planning cycles in PR agencies and corporate communications departments. January brings new goals, new client relationships, new campaign briefs. By March, teams have encountered their first major challenges and adjusted their working patterns accordingly. By June, summer staffing changes disrupt established rhythms. By September, the pressure to close out the year strong intensifies. A quarterly audit captures how these predictable stressors affect team dynamics, creating opportunities to intervene before stress degrades into dysfunction.

Regular audits make resource management visible and actionable. When the team notices that psychological safety scores dropped in the month following a major client loss, they can investigate why. Perhaps leadership communicated the news in a way that made team members feel personally blamed, or perhaps the response involved rapid restructuring that left people uncertain about their job security. Identifying the mechanism allows the team to address it directly and prevent the same pattern from recurring during the next crisis.

The field research on high-performing teams provides external reference points that help teams assess whether their self-audit results indicate genuinely strong performance or simply reflect lower standards than top performers maintain.

Google's Project Aristotle identified specific behavioral markers that distinguished their highest-performing teams. Members took roughly equal turns speaking in meetings and discussions. No single voice dominated, and no one consistently stayed silent. This equality in conversational turn-taking correlated strongly with team success, independent of the particular people involved or the specific projects they tackled (Google's Project Aristotle, 2016).

The research team also found that high-performing team members demonstrated higher social sensitivity. They picked up on subtle emotional and social cues from teammates, noticed when someone seemed confused but hesitant to ask for clarification, and recognized when a team member's silence indicated disagreement rather than agreement. This attentiveness allowed teams to surface and address issues quickly, before small misunderstandings compounded into larger conflicts.

For PR teams running self-audits, these markers offer concrete targets. Track who speaks in team meetings over several sessions. If the same three people contribute 80 percent of the discussion, regardless of the topic, the team has a participation inequality problem. Track how often team members explicitly check in about emotional reactions to news or decisions. "How are people feeling about this direction?" matters as much as "What do you think about this direction?" If those check-ins never happen, social sensitivity likely runs lower than research suggests it should.

The checklist and audit worksheet are designed to fit into busy schedules without adding complexity, so reflection and realignment stay a core part of team development rather than becoming another burdensome administrative requirement.

Start small with a 30-minute session focused on one dimension of team functioning. Psychological safety makes a logical starting point because it enables progress on other dimensions. Have each team member independently rate their perception of current psychological safety using five specific questions:

These items come from Edmondson's validated psychological safety scale. After individual rating, share scores anonymously and discuss the patterns. What specific behaviors or situations contributed to high scores? What reduced them? Most importantly, what can the team control and change versus what requires broader organizational shifts?

Document three concrete actions the team commits to trying before the next audit. Make them specific and measurable. "In weekly team meetings, everyone will speak at least twice about substantive topics, and the meeting leader will explicitly invite input from anyone who has not yet contributed" works better than "communicate better." "When receiving critical feedback, we will ask at least two clarifying questions before responding with our perspective" beats "be more open to feedback."

Track whether these commitments actually happen. Research on organizational change demonstrates that intention without implementation produces no improvement. The act of tracking creates accountability and surfaces barriers quickly. If the team commits to equal participation but consistently runs out of time before everyone can contribute, that reveals a time management problem that needs separate attention.

Expand to additional dimensions in subsequent audits. Feedback quality, role clarity, and decision-making authority each deserve focused examination. The research literature offers validated measurement approaches for each construct, allowing teams to move beyond generic impressions toward systematic assessment.

The academic research on team effectiveness has matured considerably over the past two decades. The 2017 meta-analysis by Frazier and colleagues analyzed 136 independent samples involving over 22,000 individuals and nearly 5,000 groups. The research confirmed that psychological safety predicted team learning behavior, creativity, and performance across diverse contexts, team types, and organizational settings. The effect sizes were moderate to large, meaning psychological safety explained meaningful variance in outcomes beyond what other factors accounted for. Industry sector, team size, and geographical location moderated the effects only minimally, suggesting that psychological safety functions universally rather than as a context-specific phenomenon (Frazier et al., 2017).

Performance improves by molding the internal climate and encouraging uninterrupted idea flow, deeper trust, and a clear sense of progress. The research evidence across organizational psychology, team science, and technology innovation all points in the same direction. Psychological safety enables the learning behaviors, creative risk-taking, and collaborative problem-solving that drive performance in complex, uncertain work environments.

For a downloadable checklist and audit worksheet to run your own team self-audit, visit: Self Help Team Assessment at www.piar.co/resources.

…

Tanzeel “Tan” Sukhera is the Co-founder & CEO of Piar. Tan is based in Montreal, and has 7 years of experience in Media Monitoring & Social Listening, PR & Comms Measurement, Strategy &Analysis. Through events and workshops, Piar helps PR and communication leaders apply behavioral decision science to real-world campaigns, messaging, and stakeholder work. Learn more or reach out at piar.co.

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/tsukhera/ 👈