We're working on getting insights, tools, and techniques straight to your inbox on a weekly basis. No commitment required, we'll reach out again when we're ready to see if you still want to receive weekly emails.

By submitting this form, you agree to receive recurring marketing communications from Piar at the email you provide. To opt out, click unsubscribe at the bottom of our emails. By submitting this form, you also agree to our Terms & Privacy Policy

Teams that shape media narratives face layered constraints: tight deadlines, stakeholders with different priorities, and reputations on the line. Within these everyday pressures, bias creeps in quietly. Review checkpoints focused on bias are one of the most effective ways to push attention past assumptions and surface new possibilities during campaign planning.

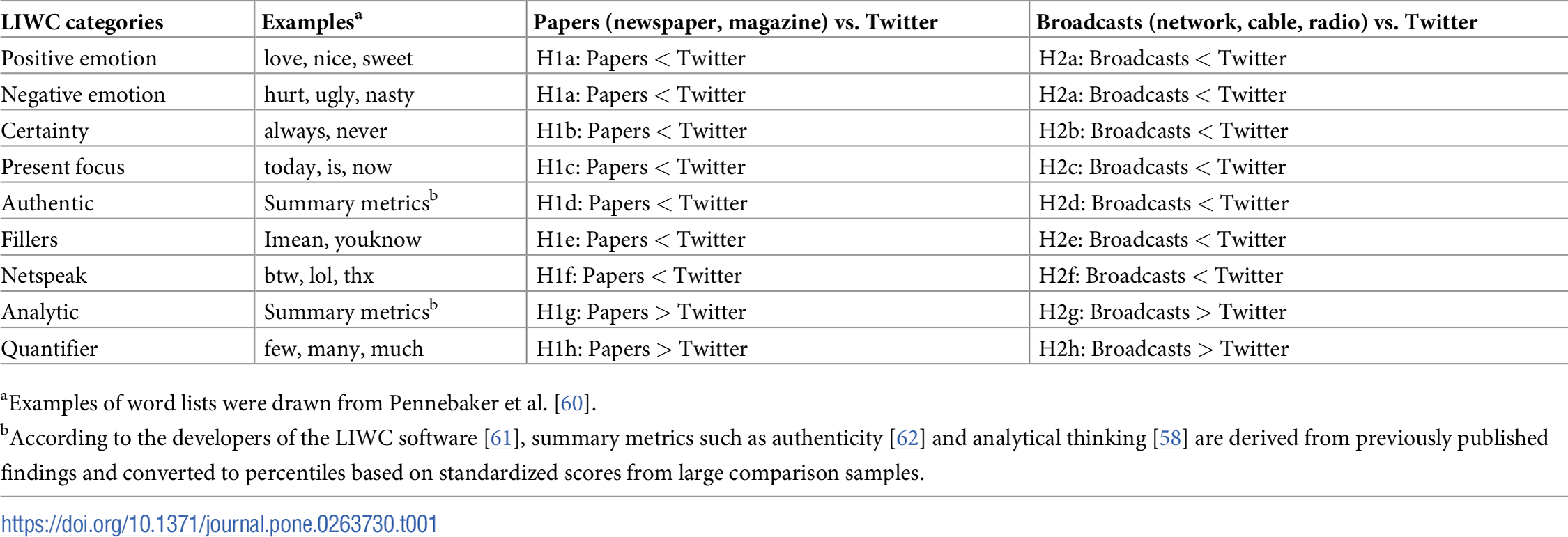

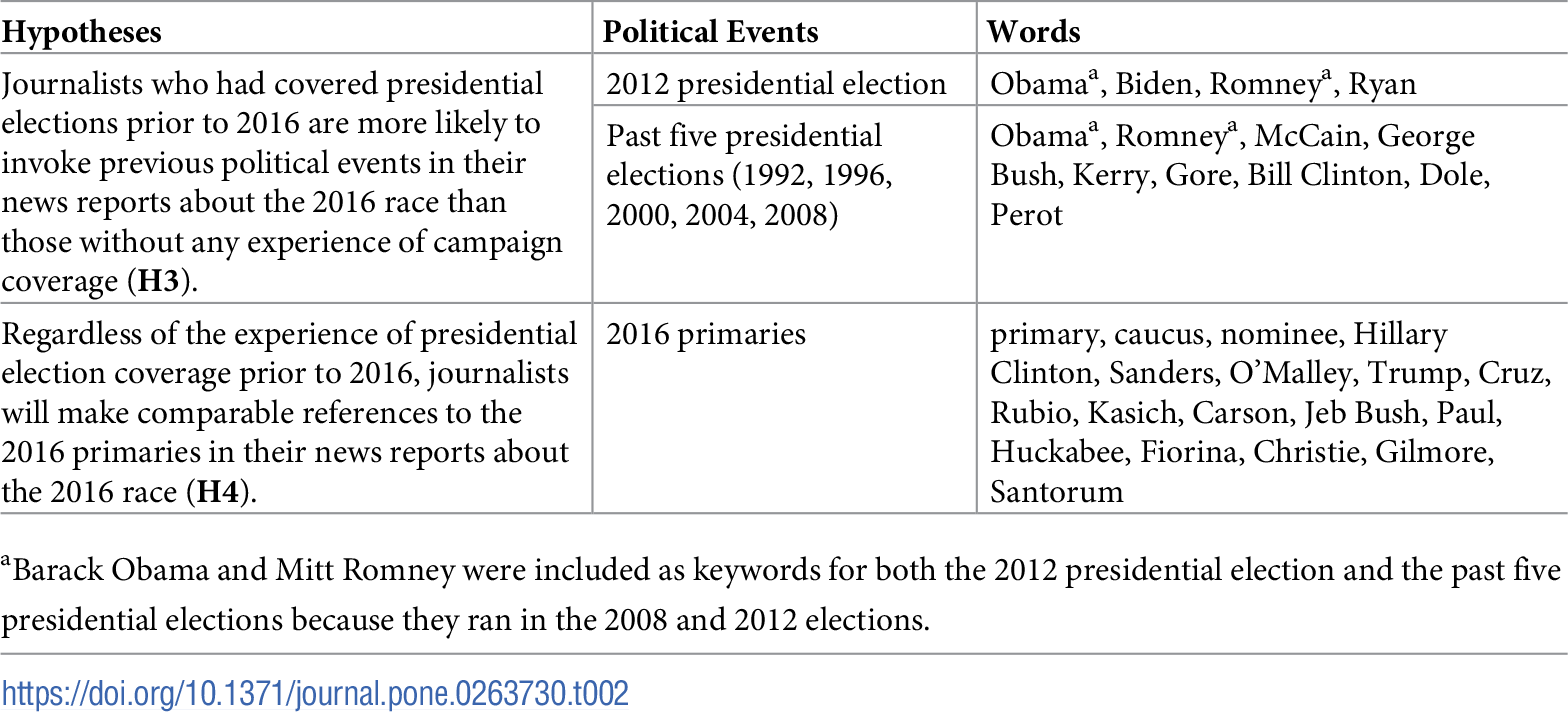

Research demonstrates that journalism and communications work inherently promotes conditions where cognitive bias thrives. A 2022 study published in PLOS One examining journalists' word choices found that journalism is inherently "institutionalized heuristic decision making" because System 1 thinking becomes embedded in journalism practices due to the rapid nature of work and recurring deadlines. System 1 thinking represents rapid, low-effort, intuitive decision-making often based on emotions and habits, while System 2 processes information more slowly and analytically.

The research found that journalists routinely engage in System 1 thinking when covering evolving events, and this thinking becomes especially amplified when navigating social media to engage with audiences in fast and personalized ways. Reporters under increasing time pressure relied on fewer sources, conducted less cross-checking, and became more dependent on public relations and politicians for news sources. These patterns apply directly to communications professionals planning campaigns under similar time constraints and deadline pressures.

Research from Boston University demonstrates that confirmation bias significantly influences reporter assessments of whether a story is worth pitching and editor decisions to greenlight story pitches. If the pitch gets accepted, confirmation bias can determine the questions a reporter decides to ask or declines to ask while investigating the story. It affects editor choices to assign certain stories to one reporter versus another. Communications teams face identical dynamics when selecting media channels, evaluating pitch angles, or prioritizing campaign messages.

The consequences extend beyond media relations. A comprehensive review examining cognitive biases across management, finance, medicine, and law found that a dozen cognitive biases impact professional decisions in these four areas, with overconfidence being the most recurrent bias. Five studies showed associations between cognitive biases (anchoring, information bias, overconfidence, premature closure, representativeness, and confirmation bias) and errors in professional judgment. Communications professionals operate within this same framework, making decisions that affect organizational outcomes while vulnerable to the same systematic biases.

Research on cognitive bias mitigation demonstrates that structured interventions can produce meaningful improvements in decision quality. A landmark 2015 study published in Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences found that participants who received a single training intervention through a computer game addressing bias blind spot, confirmation bias, and fundamental attribution error showed medium to large debiasing effects immediately (31.94% reduction) that persisted at least two months later (23.57% reduction). Games that provided personalized feedback and practice produced larger effects than passive video instruction.

Critically, these debiasing effects were domain general, meaning bias reduction occurred across problems in different contexts and problem formats that were taught and not taught in the interventions. The research demonstrated that a single training intervention can improve decision making when used alongside improved incentives, information presentation, and nudges.

A 2019 naturalistic experiment with 318 graduate students found that debiasing training improved decisions in field settings where reminders of bias were absent. Trained participants were 29% less likely to choose inferior hypothesis-confirming solutions than untrained participants. Analysis suggested that a reduction in confirmatory hypothesis testing accounted for improved decision making. This finding matters for communications teams because it demonstrates that bias training transfers to real-world professional contexts without requiring constant reminders or supervision.

Research published in Frontiers in Psychology examining analogical debiasing methods found that training techniques can achieve lasting improvement in decision skills related to a wider array of cognitive biases. The study tested whether training effects persisted four weeks after intervention, finding that interactive analogical training produced measurable improvements that extended beyond the immediate training period. This research supports implementing recurring bias reviews rather than one-time workshops, as repeated exposure reinforces pattern recognition and mitigation strategies.

Irving Janis coined the term "groupthink" in 1972 to describe when members of small cohesive groups tend to accept a viewpoint or conclusion that represents a perceived group consensus, whether or not group members believe it to be valid, correct, or optimal. Research from Yale University and other institutions identified eight symptoms of groupthink that communications teams should watch for during planning sessions.

These symptoms include an illusion of invulnerability or the inability to be wrong, collective rationalization of the group's decisions, unquestioned belief in the morality of the group and its choices, stereotyping of relevant opponents or out-group members, and the presence of "mindguards" who act as barriers to alternative or negative information. Decision-making affected by groupthink neglects possible alternatives and focuses on a narrow number of goals, ignoring the risks involved in a particular decision. It fails to seek out alternative information and is biased in its consideration of available information.

A scoping review published in BMC Research examining groupthink among healthcare teams found that groupthink could occur at all levels of organizational hierarchy. For example, if a team member observes that the working approach does not explain all factors but does not mention this concern due to the assumption that the group's thought process must be correct, this group exhibits groupthink. The review found that groupthink emerged as a bias contributing to continued use of problematic practices, with the need to belong with senior colleagues superseding the need for better approaches.

Research demonstrates that individuals with strong identification to their group are more likely to express concerns with group decisions, while those who weakly identify with the group are more likely to change their opinion to fit their perceptions of other members' feelings. This creates a discrepancy between individual and public concerns, particularly when someone believes other members share the same opinions. Communications teams should recognize these patterns when junior team members remain silent during planning sessions or when dissenting voices disappear once senior leaders express preferences.

Beyond groupthink, research from the Nielsen Norman Group identifies the common-knowledge effect as a harmful bias in team decision-making. Teams often make worse decisions than individuals by relying too much on widely understood data while disregarding information possessed by only a few individuals. Psychologists Garold Stasser and William Titus found that teams often do not live up to their decision-making potential. Instead of harnessing members' collective resources to make robust decisions, teams spend most of their time discussing information they all already know and not enough time on uniquely held information.

This phenomenon has been consistently confirmed by psychology researchers over four decades. The common-knowledge effect represents a decision-making bias where teams overemphasize the information most team members understand instead of pursuing and incorporating unique knowledge of team members. In communications planning, this manifests when teams default to familiar media channels, messaging approaches, or targeting strategies because everyone understands them, while specialized knowledge about emerging platforms, niche audiences, or innovative tactics gets overlooked because only one or two team members possess that expertise.

Research by Susanne Abele and colleagues found that members who share more knowledge with other team members were "cognitively central" and seen as more credible and influential in discussions. This creates a problematic dynamic where team members with unique, potentially valuable information may hesitate to share it because they recognize they lack the social capital or perceived credibility of more central team members. Communications leaders must actively create space for peripheral team members to contribute specialized knowledge that could strengthen campaign outcomes.

Anchoring bias describes the human tendency to rely too heavily on one piece of information when making decisions. In foundational research by Kahneman and Tversky published in 1974, participants were shown random numbers before estimating percentages of African countries in the United Nations. The group that received an initial number of 10 had a median estimate of 25%, while the group that received an initial number of 65 had a median estimate of 45%. Both groups' estimations were clearly influenced by their starting values, giving uneven weight to the initial value and causing final estimates to be swayed toward that initial value.

For media planning, anchoring bias appears when teams fixate on the first creative concept presented, the initial budget figure discussed, or the first channel recommendation made. Research demonstrates that even when people know about anchoring and are explicitly forewarned about its effects, the bias still affects their judgment. A study published in JAMA Internal Medicine examining physician decision-making found that doctors were less likely to test for pulmonary embolism when initial patient information mentioned congestive heart failure, demonstrating how initial information creates anchors that bias subsequent clinical decisions even among highly trained professionals.

Research on anchoring in organizational settings found that even experienced legal professionals were affected by anchoring, remaining true even when the anchors provided were arbitrary and unrelated to the case in question. Participants who were explicitly informed that anchoring would contaminate their responses and told to do their best to correct for it still reported higher estimates than control groups that received no anchor. This demonstrates that awareness alone does not eliminate anchoring effects, supporting the need for structured debiasing processes rather than simply informing teams about bias existence.

The consider-the-opposite strategy has emerged as one of the most reliable methods for mitigating anchoring bias. Research published in Decision Support Systems found that the consider-the-opposite strategy effectively debiases the anchoring effects of recommendations in decision-making. This approach involves systematically considering alternative explanations, opposing viewpoints, and contradictory evidence before finalizing decisions.

Confirmation bias represents the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses. A study examining cognitive biases in fact-checking involving twelve journalists and fact-checkers from different organizations found that confirmation bias ranked among the six most relevant biases affecting professional verification processes, alongside anchoring, availability, selection, source bias, and reinforcement effect.

Research demonstrates that when asking a question, testing a hypothesis, or questioning a belief, people exhibit confirmation bias by being more likely to search for evidence that confirms rather than disconfirms what they are testing. They also interpret evidence in ways that confirm rather than disconfirm their beliefs and perceive confirming evidence as more important than disconfirming evidence. This pattern applies directly to media planning when teams favor channels they have successfully used before, interpret campaign metrics in ways that validate their initial strategy, or discount data that suggests their approach needs adjustment.

Research from Scientific American examining how cognitive biases make people vulnerable to misinformation identified three types of bias that make the social media ecosystem vulnerable to both intentional and accidental misinformation. Cognitive biases originate in how the brain processes information encountered every day. The brain can deal with only a finite amount of information, and too many incoming stimuli cause information overload. This creates conditions where confirmation bias flourishes as people seek mental shortcuts to process overwhelming information flows.

The research found that algorithmic biases can amplify confirmation bias by promoting popular content regardless of quality, feeding into existing cognitive bias and reinforcing what appears popular irrespective of actual merit. These same dynamics affect media planning when teams rely on engagement metrics, impressions, or reach data that may reflect algorithmic amplification rather than genuine audience response or campaign effectiveness.

The purpose of a live bias review is simple. Gather the team before finalizing decision points and block out time to examine, together, how opinions and routines influence both ideas and choices. This works best as a recurring event, not a single workshop or postmortem. A bias review weaves itself into planning meetings, pitch development, and agency-client approvals.

Begin with clear expectations. Let everyone know the aim is not to critique creative work or analyze data alone, but to name cognitive shortcuts that can affect big outcomes. Assign one person as the review leader. Their only job is to work through a checklist or prompt sheet of common bias risks. Criteria are drawn directly from real communications experience: familiarity bias in channel selection, anchoring on the first creative draft, or groupthink hiding behind consensus.

Research on cognitive debiasing strategies outlines three groups of interventions: educational strategies that make practitioners aware of bias risks and enhance their ability to detect the need for debiasing in the future, workplace strategies that can be implemented during problem-solving while reasoning about the problem at hand, and forcing functions that create structural safeguards against bias. Educational strategies enhance future debiasing ability, workplace strategies provide real-time bias mitigation, and forcing functions create environmental conditions that reduce bias opportunities.

Research demonstrates that the ability to avoid bias correlates with critical thinking ability. Many processes described in debiasing research would be integral to building critical thinking into professional practice. Communications teams benefit from educational strategies that build bias awareness, workplace strategies that teams can deploy during active planning sessions, and forcing functions that structure decision processes to reduce bias vulnerability.

Make participation wide, not limited to leads. Research on team decision-making shows that encouraging those with less formal influence to voice questions helps counter the common-knowledge effect and groupthink dynamics. Invite team members to identify patterns in language, to push the group to revisit core assumptions, and to consider how recent events might be shaping urgency or selection pressures. Write observations on a visible board or digital document. Use specific campaign examples where bias may have shaped coverage outcomes or media priorities.

Research examining debiasing interventions found that organizations can combine debiasing training with choice architecture techniques to improve decision quality. For example, one study tested a dual intervention combining debiasing training (prompting decision-makers to envision consequences) with choice architecture techniques (increasing salience of critical information) to improve inventory decisions. Another tested combining debiasing thinking strategy training with visualization of priorities to improve transportation decisions. Communications teams can adapt these approaches by combining bias awareness training with structured decision frameworks that make critical factors visible and salient during planning sessions.

The review closes by building a brief action list. Any areas with clear risk receive a plan, even if that plan involves scheduling another round of feedback, consulting additional stakeholders, or testing alternative approaches before finalizing decisions. This action-oriented close transforms abstract bias awareness into concrete steps that improve campaign outcomes.

Research demonstrates that debiasing interventions produce measurable improvements in decision quality. The 2015 study on debiasing training found that games providing personalized feedback and practice produced debiasing effects that persisted at least two months after intervention. Videos showing instructional content also produced meaningful effects, though smaller than interactive training. Both approaches demonstrated that bias reduction occurred across problems in different contexts and formats, suggesting that skills developed through bias review transfer to varied communications challenges.

Teams can track the impact of bias reviews through several metrics. Document the number of alternative approaches considered before finalizing decisions. Track how often initial recommendations change after bias review versus plans that skip review processes. Monitor whether campaigns that underwent bias review show different performance patterns compared to campaigns planned without review. Gather team member feedback on whether bias review processes surface concerns or alternatives that would otherwise remain unspoken.

This form of check shapes not only immediate outcomes but also future habits and values. Campaigns planned with bias review produce messaging with stronger fit for audience realities and fewer last-minute changes forced by unexamined assumptions. Research on analogical debiasing suggests that repeated exposure to debiasing frameworks helps people recognize structural similarities between training examples and new situations, improving their ability to apply debiasing strategies across varied contexts without explicit prompting.

Over time, bias review becomes embedded in team culture rather than feeling like an additional task. Team members begin recognizing bias patterns without formal review sessions. Conversations shift toward questioning assumptions and considering alternatives as default practices rather than special procedures. This cultural shift represents the most valuable outcome of structured bias review, transforming how teams think rather than just changing isolated decisions.

If you work anywhere in communications, you might find this Bias Spotter useful. It breaks down common biases that show up in messaging, campaign planning, and approvals. Each bias comes with questions you can use in meetings or reviews to notice where these patterns pop up.

The tool includes specific prompts for identifying:

Research supports using structured tools and checklists to reduce cognitive bias in professional decision-making. Studies examining forcing functions demonstrate that checklists, decision aids, and structured frameworks create environmental conditions that make biased thinking more difficult and analytical thinking easier. These tools work not by changing how people think but by changing the decision context in ways that naturally promote better outcomes.

Download and use it for free at the resource link above.

…

Tanzeel “Tan” Sukhera is the Co-founder & CEO of Piar. Tan is based in Montreal, and has 7 years of experience in Media Monitoring & Social Listening, PR & Comms Measurement, Strategy &Analysis. Through events and workshops, Piar helps PR and communication leaders apply behavioral decision science to real-world campaigns, messaging, and stakeholder work. Learn more or reach out at piar.co.

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/tsukhera/ 👈